The demand for high-impact visual effects in the label and packaging industry has pushed printing technology to its limits. Modern narrow-web converters now frequently produce labels with tactile textures, high-build varnishes, and dense pigment layers. These “thick” ink structures offer a premium feel but introduce significant technical hurdles during the UV curing process. Achieving a full cure through a 50-micron varnish layer differs fundamentally from curing a standard 2-micron offset ink film. Understanding how UV energy interacts with these dense structures determines the success of the final product.

The Physics of UV Penetration in Dense Ink Films

UV curing relies on the interaction between photons and photoinitiators. In a standard thin-film application, photons easily reach the bottom of the ink layer. However, as the ink thickness increases, the upper layers of the ink or varnish begin to absorb a disproportionate amount of energy. This phenomenon creates a “shielding effect.”

In thick-film applications like rotary screen printing or high-build flexo, the top surface may appear hard and dry while the base remains liquid. This “undercure” leads to catastrophic failures such as poor adhesion, ink flaking, or migration issues in food packaging. To solve this, engineers must look at the spectral output of their curing system.

Longer wavelengths, particularly in the UVA and UVV range (365nm to 405nm), possess better penetration capabilities. Shorter wavelengths (UVC) are mostly absorbed at the surface. Therefore, curing a thick, layered structure requires a balanced spectral recipe that ensures both surface hardness and deep-root adhesion.

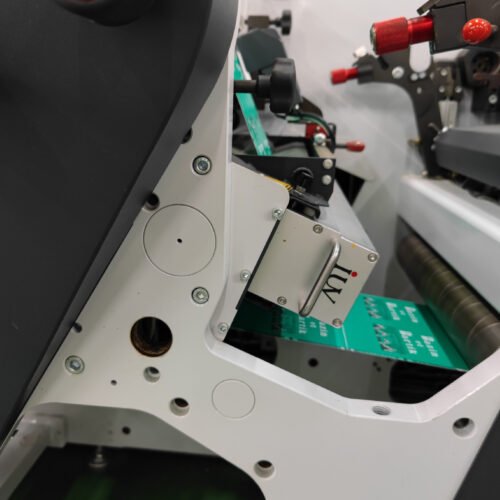

LED Curing: A Game Changer for Thick Ink Layers

The shift from traditional mercury vapor lamps to LED UV technology has revolutionized how we handle thick ink structures in narrow-web and flexo printing. Traditional lamps emit a wide spectrum of light, including a lot of infrared heat. Excessive heat can distort thin film substrates commonly used in label printing.

LED systems provide a monochromatic output, usually centered at 385nm or 395nm. These specific wavelengths are highly effective at penetrating deep into thick ink deposits. Because LED lamps do not emit UVC, the risk of “surface-only” curing is reduced. When running high-speed flexo lines with opaque whites or heavy blacks, LED energy reaches the substrate interface more efficiently than mercury systems.

Furthermore, the high peak irradiance of LED lamps allows for faster polymerization. In a layered environment, where multiple colors are printed “wet-on-dry” or “wet-on-wet,” the intensity of the LED light ensures that the energy dose (mJ/cm²) is sufficient to overcome the optical density of the pigments.

Pigment Loading and the Challenge of Opaque White

In the label industry, printing on clear or metallic substrates requires a heavy layer of opaque white. This white ink acts as a foundation for all subsequent colors. However, titanium dioxide—the primary pigment in white ink—is a powerful UV reflector and absorber.

If the white base is not fully cured, every layer printed on top of it is at risk. This is the “foundation problem” in layered ink structures. If the bottom layer is soft, the top layers will eventually crack or peel when the label is flexed.

To manage this, engineers often utilize dual-curing strategies. Using a high-output LED lamp for the white base ensures deep penetration. Subsequent CMYK layers, which are thinner, can then be cured using either LED or traditional UV. The key is to match the photoinitiator package in the ink to the specific wavelength of the lamp.

Flexographic vs. Offset: Curing Dynamics

The curing behavior changes significantly between flexo and offset processes.

Flexographic Printing

Flexo is the backbone of narrow-web label printing. It handles a wide range of ink film thicknesses. When printing thick tactile varnishes via flexo, the volume of the anilox roller determines the ink deposit. High-volume aniloxes create “peaks” of ink. If the UV lamp is not angled correctly or lacks sufficient intensity, the shadows of these peaks might remain uncured.

Offset Printing

Offset printing uses much thinner ink films but higher pigment concentrations. The curing challenge here isn’t the thickness of a single layer, but the total density of the combined layers in a multi-color job. In high-speed narrow-web offset, the window for curing is extremely small. The ink must cure instantly to prevent set-off on the next printing station. Here, the focus is on “inter-station” curing to ensure each layer is stable before the next one is applied.

The Role of Oxygen Inhibition in Thick Layers

Oxygen inhibition is a common enemy in UV curing. Oxygen molecules in the air penetrate the top layer of the ink and terminate the free-radical polymerization process. This results in a “tacky” or greasy surface.

In thin films, oxygen inhibition can ruin the entire layer. In thick layers, the surface may remain tacky while the bottom is solid. While increasing the UV dose can help, it often leads to substrate shrinkage or brittleness. In some high-end narrow-web applications, printers use nitrogen inerting. By replacing the air around the UV lamp with nitrogen, oxygen is eliminated. This allows for a much faster cure and a harder surface finish with lower energy consumption.

Adhesion and Shrinkage in Layered Structures

One often overlooked aspect of UV curing behavior is ink shrinkage. UV inks shrink during polymerization. When you stack four or five layers of ink, the cumulative shrinkage stress can be significant.

In thick, layered structures, if the curing is too aggressive, the ink can pull away from the substrate. This results in poor tape-test results even if the ink feels dry. To mitigate this, process engineers often use “gradient curing.” They apply just enough energy at the initial stations to “pin” the ink in place, followed by a final high-power UV or LED lamp to complete the through-cure. This managed approach reduces internal stress and improves overall adhesion.

Testing and Verification for Quality Control

You cannot manage what you cannot measure. In thick-film UV curing, a simple “thumb twist” test is insufficient. Professionals use more rigorous methods to ensure the integrity of the ink structure.

- Tape Testing (ASTM D3359): This checks the bond between the ink and the substrate. If the bottom layer of a thick structure is undercured, the tape will pull the entire stack off.

- MEK Rub Test: This measures the chemical resistance and the degree of cross-linking. It is particularly important for labels used in the chemical or cosmetic industries.

- Radiometer Measurements: Using a radiometer to measure both peak irradiance (W/cm²) and energy density (mJ/cm²) is mandatory. For thick films, the energy density is the more critical metric.

- Extraction Tests: For food-grade packaging, extraction tests ensure that no uncured monomers remain in the thick ink layers, which could migrate into the product.

Future Trends: Smart Curing and Hybrid Systems

The industry is moving toward “smart” curing systems that communicate with the press. If the press speed increases, the UV or LED output increases proportionally. For thick and layered structures, this synchronization is vital.

We are also seeing the rise of hybrid systems. These presses use LED for the deep-penetrating “pinning” of thick whites and heavy colors, followed by a mercury lamp at the end of the line to provide the UVC required for high-gloss surface finishes. This “best of both worlds” approach addresses the specific curing behaviors of complex ink stacks.

Conclusion: Mastering the Depth

Understanding UV curing behavior in thick and layered ink structures is a blend of chemistry, physics, and mechanical engineering. As brand owners continue to demand more complex labels with tactile and visual depth, the printer’s ability to manage through-cure becomes a competitive advantage.

By selecting the right wavelengths, managing pigment loads, and utilizing modern LED technology, converters can produce stunning, durable results without the risks of migration or adhesion failure. The goal is always the same: a perfect cure from the surface to the substrate.