Achieving a high-end finish in narrow-web label printing depends heavily on the interaction between chemistry and light. Whether you are running a flexo press or a high-speed offset line, the UV curing process determines the final look and durability of the label. Gloss coatings provide a vibrant, glass-like shine. Matte coatings offer a sophisticated, non-reflective texture. Both require specific curing strategies to avoid common defects like “orange peel,” tackiness, or poor adhesion.

Optimizing these finishes involves more than just turning on the lamps. It requires a deep understanding of UV wavelengths, ink chemistry, and mechanical press settings.

The Science of UV Curing in Narrow-Web Printing

UV curing is a photochemical reaction. When UV light hits the liquid coating, photoinitiators absorb the energy. This triggers a chain reaction called polymerization, turning liquid into a solid film instantly.

In label printing, this process happens within milliseconds. On a narrow-web press running at 150 meters per minute, the window for curing is extremely tight. If the energy output is too low, the coating remains “undercured” and tacky. If it is too high, the substrate may warp from heat, or the coating might become brittle.

Gloss vs. Matte: The Physical Difference

Gloss coatings are designed to level out perfectly smooth. This smoothness allows light to reflect directly back to the eye. Any interruption in the curing speed can cause surface ripples, reducing the “mirror” effect.

Matte coatings contain matting agents, usually silica or wax particles. These particles create a microscopic roughness that scatters light. Curing matte coatings is often more difficult. The solid particles can shield the photoinitiators from the UV light, leading to a “surface-only” cure where the bottom layer remains liquid.

Optimizing Gloss Coatings for Maximum Clarity

To get that “wet look” on a label, the coating must flow out before it hits the UV lamp. This is the “leveling” phase.

Controlling Viscosity and Heat

Viscosity is the most critical factor for gloss finishes. If the coating is too thick, it won’t level, resulting in a textured “orange peel” effect. In flexo printing, the anilox roll selection is key. A lower BCM (billion cubic microns) roll delivers a thinner, smoother layer.

Temperature also plays a role. In traditional mercury vapor systems, the heat from the lamps can actually help the coating flow. However, with LED UV curing, there is very little infrared heat. You might need to pre-heat the coating or the substrate to achieve the desired flow.

Managing Surface Tension

If the surface tension of the substrate is lower than the coating, the liquid will bead up. This is known as “crawling.” Use corona treatment on films like BOPP or PE to raise the surface energy. A target of 38 to 42 dynes is usually standard for UV gloss applications.

Challenges with Matte Coatings and Oxygen Inhibition

Matte coatings are notorious for “scuffing.” If they are not cured correctly, the matting agents can be rubbed off the surface easily.

The Problem with Oxygen

Oxygen inhibition is the biggest enemy of a perfect matte finish. Oxygen molecules at the surface of the coating can scavenge the free radicals needed for curing. This leaves a thin, greasy layer on top.

In matte finishes, this inhibition is more pronounced because the matting agents increase the surface area exposed to air. To solve this, many high-end narrow-web printers use nitrogen inerting. By replacing the air around the UV lamp with nitrogen, you eliminate oxygen. This results in a much harder, more scratch-resistant matte surface.

Wavelength Penetration

Matte coatings are thicker and more opaque than gloss. Traditional mercury lamps provide a broad spectrum of light (UVA, UVB, UVC). UVC handles the surface cure, while UVA penetrates deeper.

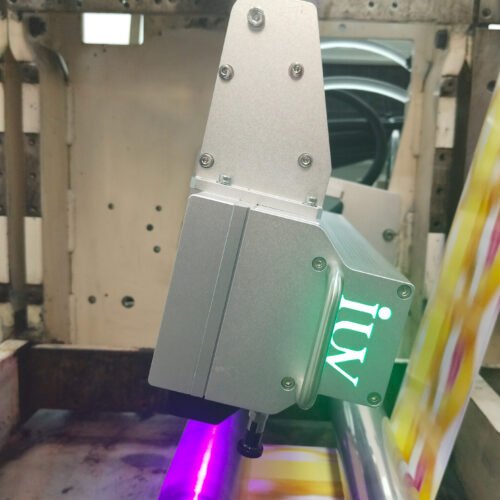

If you are using LED UV, you are likely working with a single wavelength, such as 385nm or 395nm. This light penetrates very well but can sometimes struggle with the very top surface of a matte coating. Combining LED for deep cure with a small “mercury boost” or using high-intensity 365nm LED can bridge this gap.

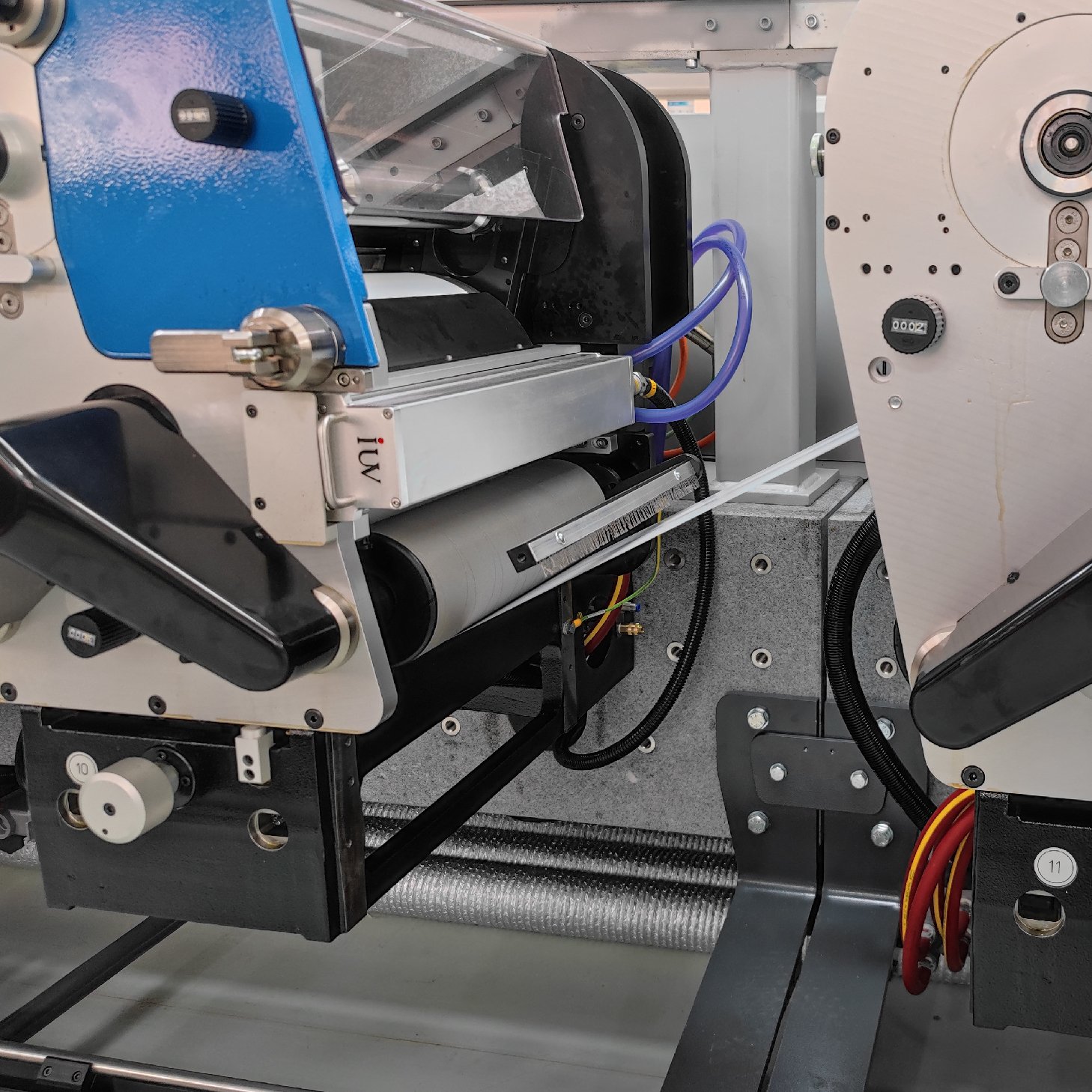

LED UV vs. Mercury Vapor: Making the Choice

The printing industry is moving rapidly toward LED UV. For label converters, the benefits are clear, but the transition requires technical adjustments.

Advantages of LED UV Curing

- Heat Management: LED lamps do not emit infrared radiation. This allows you to print on thin, heat-sensitive films without the material shrinking or melting.

- Instant On/Off: There is no warm-up time. This increases press uptime and reduces energy costs.

- Consistency: Mercury bulbs decay over time, losing intensity. LEDs provide the same output for tens of thousands of hours.

Adjusting Chemistry for LED

You cannot simply use mercury-optimized coatings under LED lamps. LED-compatible coatings contain photoinitiators that react specifically to long-wave UVA. When switching to LED for gloss or matte finishes, verify that your ink supplier has tuned the formula for 395nm or 385nm output.

Technical Parameters for Flexo and Offset Presses

Whether you are using flexo or offset, the mechanical setup must be precise.

Anilox Selection (Flexo)

For UV coatings, the anilox roll geometry is vital. Hexagonal cells are common, but elongated “S” cells or “tri-helical” patterns often provide a smoother laydown for high-viscosity matte coatings. For a standard gloss, an anilox with 300-400 LPI (lines per inch) and a volume of 4.0 to 6.0 BCM is usually effective.

Press Speed and Dose

There is a direct relationship between press speed and the “UV dose.” Dose is the total energy the coating receives. If you double the press speed, you must double the lamp intensity to maintain the same dose.

Use a radiometer to measure the millijoules (mJ/cm²) at different speeds. A common mistake is assuming the lamps are fine because they look bright. Only a radiometer can tell you if the lamps are actually delivering the energy required for a full cure.

Troubleshooting Common Curing Issues

Even with the best equipment, things can go wrong. Here is how to handle typical problems.

Adhesion Failure

If the coating flakes off when you do a tape test, it is likely undercured at the base. This is common in offset printing where the ink layer might be too thick. Ensure your lamps have enough UVA output to reach the bottom of the coating layer. Also, check if the substrate has been stored in a cold warehouse; cold material can “shock” the coating and prevent a good bond.

Yellowing of Gloss Coatings

Over-curing is usually the culprit here. If the UV lamps are too powerful for the press speed, the photoinitiators can “burn,” leading to a yellowish tint. This is particularly visible on white or clear labels. Turn down the lamp power or increase the press speed to find the “sweet spot.”

“Ghosting” or Image Carryover

In narrow-web flexo, gloss coatings can sometimes show “ghost” images from the previous station. This often happens if the ink underneath isn’t fully cured before the coating is applied. Ensure each color station has its own dedicated UV lamp with enough power to pin the ink.

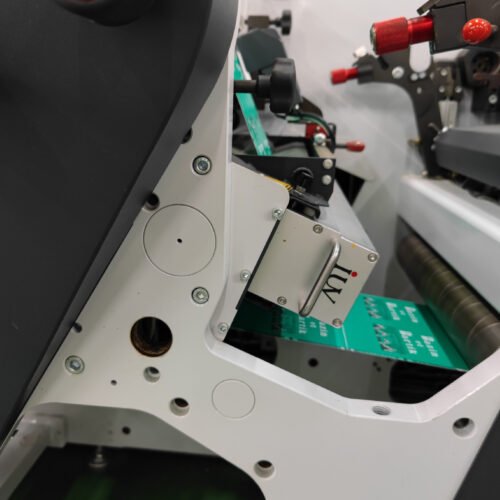

Maintenance for Long-Term Success

UV systems are “out of sight, out of mind” until they fail. A strict maintenance schedule is necessary for high-quality labels.

- Reflector Cleaning: In mercury systems, the reflectors focus 80% of the energy. If they are dusty or smoked, the cure will fail even with a new bulb. Clean them weekly with isopropyl alcohol.

- Chiller Health: LED systems and high-power mercury lamps are water-cooled. Ensure the chiller is running at the correct temperature. Overheating will cause LED chips to fail or mercury lamps to bow.

- Bulb Replacement: Mercury bulbs usually last 1,000 to 1,500 hours. Keep a log of hours and replace them before they reach the end of their life.

The Role of Substrates in Curing

The material you print on affects how UV light behaves. Paper substrates absorb some of the coating, which can dull a gloss finish. You may need a “primer” or a more generous coating volume on paper.

Synthetic films like PP or PET reflect UV light back up through the coating. This “back-scatter” can actually help the curing process, making films easier to cure than porous papers. However, films are more prone to static. Static electricity can attract dust to a wet gloss coating before it hits the lamp, creating “pimples” on the label surface. Use anti-static bars to keep the web clean.

Conclusion: Balancing Speed and Quality

Optimizing UV curing for matte and gloss coatings is a balancing act. You must align the chemistry of the coating with the wavelength of the lamps and the mechanical speed of the press.

For gloss, focus on flow, leveling, and surface energy. For matte, focus on overcoming oxygen inhibition and ensuring deep light penetration through the matting agents. By monitoring your UV dose and maintaining your equipment, you can produce consistent, high-durability labels that meet the demands of the modern market.

Transitioning to LED UV offers significant advantages in stability and heat control, but it requires a dedicated approach to ink selection and process monitoring. Stay focused on the technical data—measure your UV output, test your adhesion, and adjust your anilox rolls—to master the art of the perfect finish.