WE ARE IUV!

We Lead The

Innovation of UV Technology

We not only provide a curing system, but also

provide a cost saving and process enhancing

solution to printing, coating and converting industry.

IUV WORKS FOR

Offset Printing

Offset Printing

Offset Printing

Offset Printing

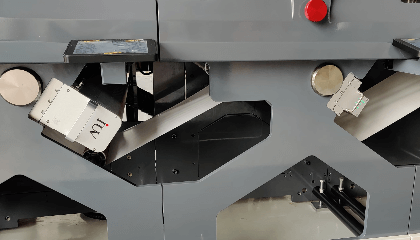

The hybrid system offer a flexible solution to match the different printing requirement.

LED UV is the inevitable trend in printing, coating and converting industries.

Mercury UV curing lamp is valuable for the printing industry ,and IUV optimized it.

The hybrid system offer a flexible solution to match the different printing requirement.

WHY CHOOSE IUV

Choose IUV, Choose the Future of Printing!

Innovation

As a pioneer in the field of LED curing, innovation is embedded in the DNA of IUV's product team.

At IUV, we continuously push boundaries to develop cutting-edge LED UV solutions lead the industry. We firmly believe that innovation is the driving force of our growth and success.

Concentration

IUV focuses on one thing and does it with excellence—creating top-tier LED UV curing systems.

Our dedication and professionalism have enabled us to set the benchmark in the industry.

By staying focused, we continuously refine our expertise to meet evolving customer needs.

Cooperation

Customer-centricity is at the core of everything IUV does.

We work closely with our clients, constantly seeking ways to improve outcomes. This collaborative approach not only enhances our products but also drives IUV’s continuous improvement.

Modularity

Our products are designed with a modular approach to simplify customer usage and management.

Modular systems offer flexibility and scalability, making it easier for clients to adapt to changing business needs. This design philosophy helps reduce operational costs while maintaining efficiency.

Quality

IUV is committed to manufacturing UV curing systems of the highest quality.

Our rigorous quality standards and best-in-class service ensure reliable, long-lasting solutions. Every product we create is built to deliver superior performance and value.

Support

We prioritize long-term customer care and offer ongoing support and upgrades.

Our goal is to ensure that every UV-curing system operates at peak efficiency throughout its lifecycle. With IUV, customers can count on dependable service and continuous improvements.

IUV GLOBAL SERVICE NETWORK

Customer-centricity is at the heart of IUV!

Our commitment to exceeding customer expectations drives our innovation and service excellence

Looking for more global partners of lUV.

Together, we can drive growth, innovation, and success in the UV curing industry.

Looking For Premium UV Curing Solution?

Contact With IUV Experts Now!

and help you with the most suitable LED UV curing solution for you!

Contact IUV Experts

4 lampes UV LED (1,6 kW) : IUV assure d’excellentes économies sur Nilpeter FB

Nilpeter

Revolutionizing Flexo Printing withInterchangeable UV curing

OMET

The project’s success with IUV ability to enhance print quality, increase productivity, and sustainability.

Bobst

With IUV’s LED UV curing system, enhanced production capabilities, and sustainability.

Gallus

IUV’s LED UV retrofit for fast curing , energy savings, and extended equipment lifespan.

Mark Andy

The UV LED upgrade for the MPS EF-430 is a testament to efficiency and sustainability.

MPS