The physics of a perfect print job often comes down to a few microns of chemistry. In flexographic and narrow-web printing, the interaction between ink and substrate determines whether a label looks premium or ends up in the scrap bin. While most operators focus on plate pressure or anilox volumes, the real magic—and the real trouble—happens during the curing stage. Understanding how UV curing influences surface tension and wetting in flexographic printing is the difference between a high-speed success and a costly adhesion failure.

The Foundation of Wetting: Dyne Levels and Surface Energy

To understand how UV curing changes the game, we first need to look at the baseline. Wetting is simply the ability of a liquid to maintain contact with a solid surface. In label printing, we measure this using surface tension (for the ink) and surface energy (for the substrate). We typically use “dynes” as our unit of measurement.

For an ink to spread evenly, the substrate’s surface energy must be significantly higher than the ink’s surface tension. If the substrate is at 38 dynes and the ink is at 40, the ink will bead up. It’s like water on a freshly waxed car. In flexo printing, we usually aim for the substrate to be at least 10 dynes higher than the ink. UV curing introduces a dynamic variable to this equation that many engineers overlook.

How UV Curing Alters the Surface Landscape

UV curing is a photochemical process. When UV light hits the liquid ink, photoinitiators absorb the energy and begin a chain reaction called polymerization. This happens in fractions of a second. However, this reaction does more than just turn liquid to solid. It physically and chemically alters the surface of the printed layer.

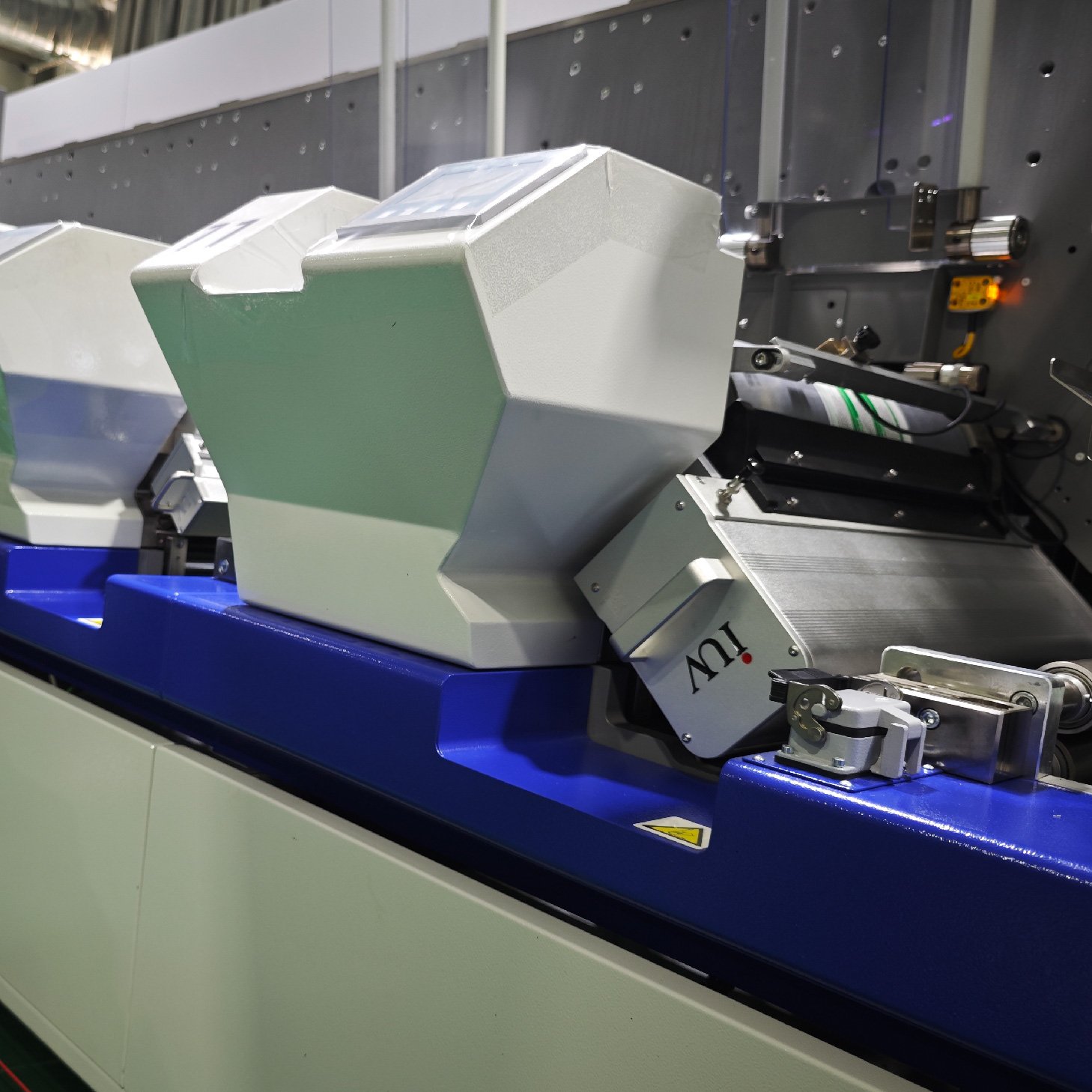

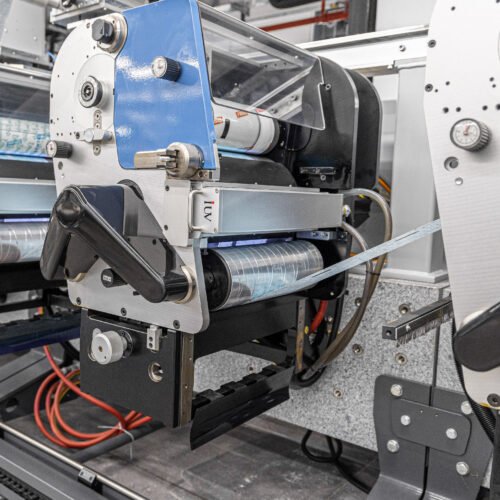

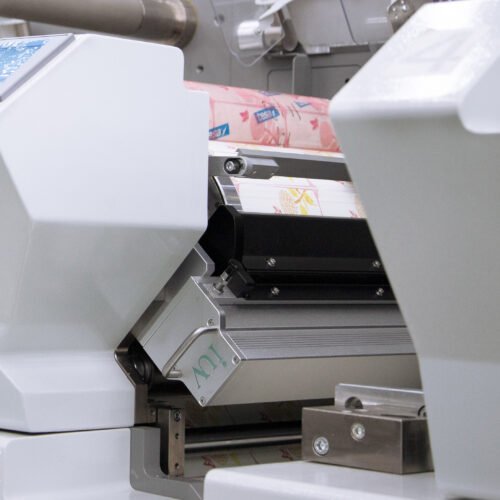

In multi-station narrow-web presses, we often print “wet-on-dry.” This means the first color is printed and cured before the second color hits it. The first UV lamp changes the surface energy of that first layer of ink. If the UV output is too high, or if the ink chemistry isn’t optimized, the cured ink surface can become “over-cured.” An over-cured surface often has very low surface energy, making it nearly impossible for the next ink station to wet out properly. This leads to pinholing or poor inter-coat adhesion.

The LED UV Revolution: A Different Thermal Profile

Traditional mercury arc lamps have been the workhorse of the industry for decades. They emit a broad spectrum of light, including a significant amount of infrared (IR) radiation. This heat can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, heat can lower the viscosity of the ink, momentarily improving wetting. On the other hand, excessive heat can cause thin film substrates used in label printing to stretch or deform.

LED UV curing operates differently. It provides a narrow wavelength (usually 365nm or 395nm) and generates almost no IR heat toward the substrate. Because the substrate stays cool, the surface tension of the ink remains more stable during the curing window. For narrow-web printers working with heat-sensitive films like PE or PP, LED UV offers a much more predictable wetting environment. You don’t have to fight the “heat-induced” fluctuations in dyne levels that plague mercury systems.

Inter-station Curing and the “Trapping” Challenge

In flexographic printing, “trapping” refers to the ability of one ink layer to stick to another. UV curing influences this directly. When we cure an ink station, we aim for a specific degree of cross-linking.

If we achieve 100% full cure at an inter-station lamp, the surface might become too chemically inert. The next ink layer has nothing to “grab” onto. Professional engineers often look for a “sweet spot”—a state where the ink is dry to the touch and stable, but still possesses enough surface reactivity to bond with the subsequent station. This is often referred to as “green strength” or “under-curing” the intermediate stations to favor better wetting of the top layers.

Surface Tension in Offset vs. Flexo Applications

While flexo is dominant in narrow-web labels, UV offset (or litho) printing also deals with these surface tension hurdles. In offset, the ink films are much thinner than in flexo. Because the film is thin, the influence of the UV curing process on surface energy is even more pronounced.

In flexo, the anilox roller dictates the volume, giving us a thicker cushion of ink. If the surface tension is slightly off, the volume can sometimes compensate. In UV offset or narrow-web hybrid presses, the margin for error is slimmer. The rapid polymerization of UV offset inks can cause immediate “shrinkage,” which pulls the ink away from the edges of the dots, affecting the overall wetting and final print gain.

Substrate Variables: Corona Treatment and UV Interaction

Most film substrates (BOPP, PET, PE) require corona treatment to boost surface energy before they even hit the first print station. However, the effect of corona treatment is temporary. Furthermore, the UV curing process itself can produce ozone (in the case of mercury lamps), which can further interact with the substrate’s surface chemistry.

When the UV light hits the ink, some stray light inevitably hits the unprinted areas of the substrate. This “stray” UV can sometimes cause further oxidation of the substrate, potentially increasing its surface energy but also making it more brittle. In high-speed narrow-web printing, managing this balance is vital for maintaining consistent wetting across a long production run.

Troubleshooting Wetting Issues in UV Flexo

When you see ink “crawling” or “beading” on the press, the UV system is often the first place to look, right after checking the corona treater. Here is a technical checklist:

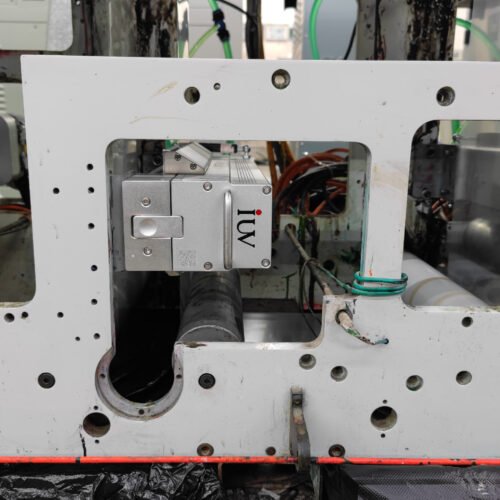

- Check Lamp Output: Are your lamps old? Degraded mercury bulbs shift their spectral output, which can lead to “surface-only” curing, leaving the bottom of the ink film wet while the top is hard. This creates a surface tension nightmare.

- Evaluate Photoinitiator Balance: If you are using LED UV, ensure your inks are specifically formulated for the narrow 395nm peak. Using mercury-optimized inks with LED lamps leads to poor cross-linking and inconsistent surface energy.

- Monitor Substrate Temperature: If the web is getting too hot, the surface energy of the film can drop. Check your chill rolls and UV shielding.

- Dyne Testing: Don’t just test the raw substrate. Test the surface of the cured ink. If the cured ink is showing a dyne level below 36, the next station will likely have wetting issues.

The Chemical Component: Surfactants and Flow Agents

Ink formulators add surfactants to UV inks to lower their surface tension, helping them flow into the “valleys” of the substrate. However, these surfactants can migrate to the surface during the UV curing process.

If too many surfactants migrate to the top of the ink film during the fraction of a second when the UV light hits, they create a “low-energy” barrier. This makes the cured ink surface very “slippery” for the next ink. This is a common reason why a white base-coat might look perfect, but the colors printed on top of it start to flake or crawl. Adjusting the UV power can sometimes lock these additives in place before they have time to migrate, improving the wetting of subsequent layers.

Future-Proofing the Pressroom

As narrow-web printing moves toward faster speeds and thinner sustainable films, the relationship between UV curing and surface physics will only become more critical. The industry is moving away from “brute force” curing with high-wattage mercury lamps. Instead, we are seeing a shift toward precision curing with LED and targeted chemistry.

Optimizing how UV curing influences surface tension and wetting in flexographic printing isn’t just a lab exercise. It is a daily operational requirement. By controlling the thermal load, monitoring dyne levels of cured films, and matching ink chemistry to the light source, printers can eliminate the most common causes of rejection in label and packaging work.

The goal is a seamless bond. When the surface tension of the ink and the surface energy of the substrate (or the previous ink layer) are in harmony, the result is a vibrant, durable, and high-quality product. This technical synergy is what defines modern, professional printing.