The shift toward high-speed, high-definition label printing has placed immense pressure on curing systems. In narrow-web environments, particularly within flexo and offset processes, achieving a perfect cure across multiple ink layers is a delicate balancing act. Multi-pass printing—where substrates receive several layers of ink, coatings, or varnishes in a single run—introduces variables that can compromise the integrity of the final product. Understanding these challenges requires a deep dive into the physics of UV and LED radiation, ink chemistry, and substrate behavior.

The Physics of Energy Delivery

At its core, UV curing is a photochemical reaction. Photoinitiators in the ink absorb specific wavelengths of light, triggering a polymerization process that turns liquid into a solid film. In a multi-pass setup, the energy must penetrate not just the top layer, but often several preceding layers to ensure total adhesion.

Traditional mercury vapor lamps provide a broad spectral output. This includes UVC for surface cure and UVA for deep penetration. While effective, the heat generated by these lamps often causes thin films to distort or stretch, leading to registration errors. On the other hand, LED curing systems offer a monochromatic output, typically at 385nm or 395nm. This narrow peak provides excellent deep curing but often struggles with surface tackiness due to oxygen inhibition.

The Challenge of Inter-Pass Adhesion

In multi-pass label printing, the first layer applied must be receptive to the subsequent layers. If the first station over-cures the ink, the surface becomes too “hard” or chemically inert. This results in poor “trapping,” where the second or third ink layer fails to bond to the previous one. This phenomenon, known as inter-pass adhesion failure, is a common headache in flexo printing.

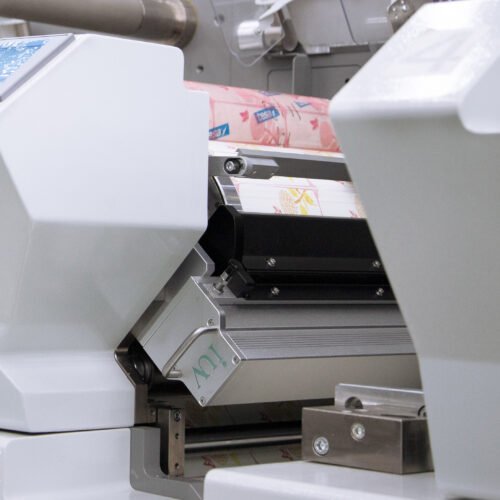

Conversely, under-curing at intermediate stations leads to “ink pick-off” on the next printing cylinder. The balance lies in managing the UV dose (total energy) and irradiance (peak intensity) at each station. Engineers must calibrate the output so that the ink is sufficiently “pinned” to stay in place but remains chemically active enough to bond with the next layer.

Oxygen Inhibition in LED Curing

Oxygen inhibition is perhaps the most significant hurdle when transitioning narrow-web presses to LED curing. Oxygen molecules at the surface of the ink film act as scavengers. They react with the free radicals produced by the photoinitiators faster than the monomers can. This leaves a greasy, uncured layer on top of an otherwise solid film.

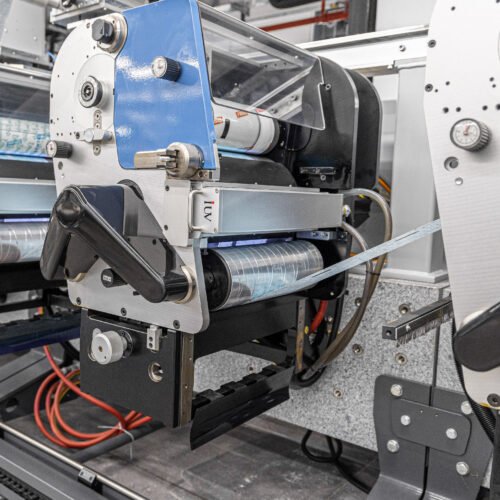

In multi-pass offset or flexo printing, this uncured surface can contaminate the rollers of the following station. High-intensity LED arrays help overcome this by flooding the surface with so many radicals that they exhaust the local oxygen supply. However, this requires precise synchronization between press speed and lamp power. If the press slows down during a roll change without adjusting the LED intensity, the heat build-up or over-exposure can still ruin the substrate.

Heat Management on Thin Films

Narrow-web printing frequently utilizes heat-sensitive materials like PE, PP, and shrink films. While LED systems are marketed as “cool” curing solutions, they still generate heat through the exothermic reaction of polymerization and the infrared energy emitted by the LEDs themselves.

In a multi-pass run involving five, six, or eight colors, the cumulative heat can be substantial. If the substrate temperature exceeds its glass transition point, it will lose dimensional stability. For high-end labels requiring tight registration, even a fraction of a millimeter of stretch can result in blurry images or ghosting. Cooling rollers (chill rolls) are often necessary, but their efficiency depends on the contact time and the thickness of the material.

Ink Chemistry and Pigment Loading

The density of the pigment significantly affects how UV light travels through the ink. Darker colors like carbon black and opaque whites are notorious for blocking UV radiation. In multi-pass printing, an opaque white base is often the first layer. If this base layer does not cure fully through to the substrate, the entire stack of colors on top will eventually delaminate.

This requires “deep-cure” photoinitiators that respond to longer wavelengths (UVA). However, these initiators can sometimes cause yellowing in clear varnishes applied in the final pass. Formulating inks that work harmoniously across all stations is a specialized task for ink chemists. They must ensure that the spectral sensitivity of the ink matches the output of the specific lamps used on the press.

The Role of Substrate Surface Tension

Successful curing is not just about the light; it is also about how the ink sits on the material. Most plastic films used in label printing have low surface energy. Before the first pass, corona treatment is often used to raise the dyne level of the substrate.

If the dyne level is too low, the UV ink will “bead up” before it hits the curing lamp. In a multi-pass process, the act of curing the first layer can sometimes change the surface energy of the remaining exposed areas. This makes the second pass behave differently than the first. Monitoring dyne levels throughout the run is vital for maintaining consistent print quality.

Migration Concerns in Food Packaging

For the narrow-web label industry, food safety is a major driver of technical standards. Incomplete curing in multi-pass printing can lead to “migration,” where unreacted monomers or photoinitiators leach through the substrate or transfer to the backside of the label when it is wound into a roll.

This is a critical risk in low-migration applications. Because multi-pass jobs involve thicker total ink deposits, the risk of having unreacted components trapped in the lower layers increases. Analytical testing, such as the “ink rub test” or more sophisticated GC-MS analysis, is necessary to verify that the curing process has reached completion across the entire ink stack.

Maintenance and Monitoring Protocols

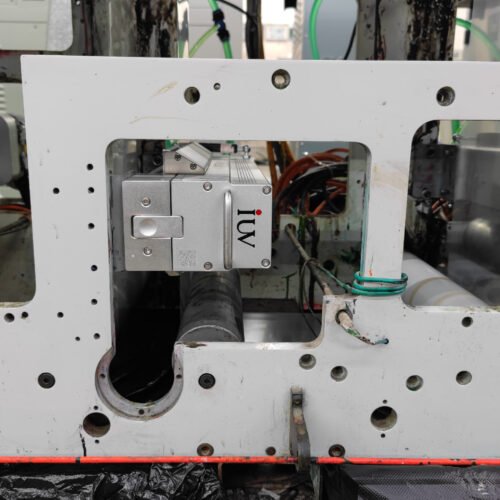

The performance of UV and LED systems degrades over time. Mercury lamps lose their intensity and shift their spectral output as the bulbs age. LED chips can fail individually, leading to “cold spots” across the web. In a multi-pass environment, a failure at a single station can ruin thousands of meters of material before the operator notices.

Implementing a rigorous maintenance schedule is the only way to mitigate this. This includes:

- Regular cleaning of reflectors and lamp glass to prevent dust build-up.

- Using radiometers to measure the actual UV dose reaching the substrate at each station.

- Monitoring water-cooling or air-cooling systems to prevent thermal spikes.

- Checking the “hours of operation” for bulbs and arrays to replace them before they hit their end-of-life drop-off.

Future-Proofing the Process

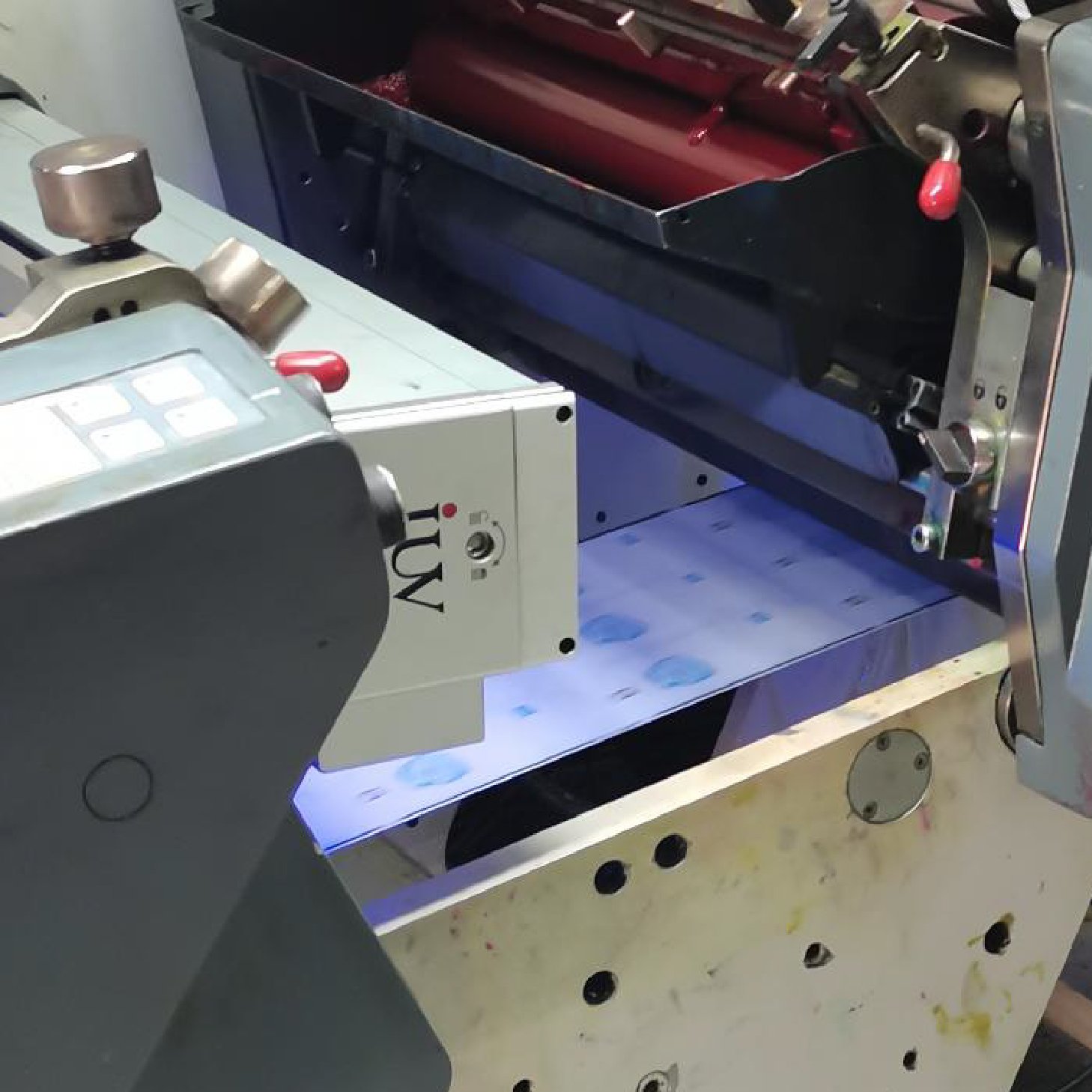

As label designs become more complex, incorporating tactile varnishes and metallic foils, the demands on UV curing will only grow. The industry is moving toward hybrid systems that combine the strengths of both mercury and LED technology. For example, using LED for intermediate “pinning” between color stations to save energy and reduce heat, while using a final mercury lamp to ensure a high-gloss, scratch-resistant surface cure.

Success in multi-pass label printing requires an integrated approach. It is not enough to simply buy the fastest press or the most expensive lamps. The engineer must synchronize ink chemistry, substrate prep, and curing parameters into a single, cohesive workflow. By understanding the physics of energy delivery and the limitations of the hardware, printers can push the boundaries of what is possible in narrow-web production.